Why Haven’t Loan Officers Been Told These Facts?

The Truth In Lending Act, An Overview of the TILA’s Original Principles

Senator Paul Douglas was the original sponsor of the Truth in Lending Act (TILA) legislation. Following his defeat in a reelection bid, Senator William Proxmire took on the role of championing the bill. The following narrative provides insight into the development of TILA disclosure practices, the intent behind these disclosures, and the consumer protections that were established.

Significant amendments like the CHARM booklet, HOEPA, MDIA, and Dodd-Frank have worked to restore the original intent of the legislation over the years. These amendments were intended to reduce risky or unsound borrowing, protect consumers from abuse, and promote competition among lenders, ultimately benefiting consumers as a whole.

Excerpted From “The Long History of “Truth in Lending”

Anne Fleming, Georgetown University Law Center

Originally, Douglas conceived of the benefits of disclosure in then-familiar terms, as advancing the same objective as the Uniform Small Loan Law: avoiding deception and warning borrowers of the high cost of credit. Douglas also briefly mentioned a secondary goal: encouraging “price competition” in the consumer credit market. But Douglas did not originally intend that the “simple annual rate,” later renamed the “annual percentage rate,” would provide an exact measure of the cost of credit so as to aid consumers in making precise cost comparisons. As he wrote to one banker in 1961, “We do not expect great accuracy in the annual percentage rate.” Rather, Douglas hoped to impress upon borrowers a more general sense of the high cost of credit, furthering his primary goal of avoiding deception and preventing excessive borrowing. “We are concerned with letting the borrower know that the rate is 12 percent rather than 6 percent, or 18 percent rather than 1½ percent,” he explained. He fully agreed that the agency administering the bill should provide a “little leeway” for creditors, allowing rounding to the nearest whole number. In 1962, he proposed an amendment to the legislation that would allow “some flexibility or ‘approximation’ of the annual rate.

Douglas later rebranded the bill the “Truth in Lending Act,” or TILA, and renamed the disclosure metric the “annual percentage rate,” or APR. Eight years after its initial adoption, when Congress finally enacted a revised version of the measure, the bill’s stated objectives had also changed. The original 1960 preamble to the bill emphasized the goals of avoiding consumer deception and dampening demand for credit by warning of its high cost. It stated that the “excessive use of credit results frequently from a lack of awareness of the cost thereof to the user” and the “purpose” of the law was to “assure a full disclosure of such cost.” But thereafter, the bill’s “declaration of purpose” shifted, slowly pivoting away from Douglas’s original objectives.

Douglas himself amended the bill in 1963, in response to a statement from the President’s Council of Economic Advisors, to clarify that the problem was not “excessive” credit but rather the “untimely use of credit.” Four years later, after Douglas was voted out of office and Senator William Proxmire (D-Wisc.) took over the campaign for Truth in Lending in 1967, the stated “purposes” changed again, to strengthening “competition among the various financial institutions and other firms engaged in lending.” In this iteration of the bill, increasing consumer awareness of the cost of credit was not its own objective, but rather a means to increase price competition. Douglas’s 1969 statements in favor of model state credit legislation and his memoir, published in 1972, belatedly embraced this revised understanding of the primary purpose behind the bill.

Over the course of the 1960s, the dominant way of thinking about disclosure shifted from an older, individual-focused perspective toward a more modern, market-oriented one. Like the Uniform Small Loan Law of the 1910s, the 1960 Douglas bill championed disclosure as a means to prevent deception and to discourage unnecessary borrowing—two objectives that earlier generations of disclosure advocates also endorsed. According to this way of thinking, disclosure prevented problems that could arise in the interface between individual borrowers and lenders by requiring the lender to speak the truth to the borrower and the borrower to hear the true cost of taking on new debt before the transaction proceeded. But the final version of the bill, enacted eight years after the first draft appeared, emphasized a different rationale for disclosure: to encourage consumers to comparison shop for credit, thereby increasing price competition among lenders. According to this view, the primary impetus for mandating disclosure was not to protect the individual borrower from harm, but rather to ensure that borrowers’ choices, in the aggregate, spurred competition among lenders and thereby pushed down prices for all. Moreover, once the law was enacted, policymakers discovered that mandatory disclosure rules actually served a third, unintended purpose: providing consumers with a defense against debt collection lawsuits.

The Fourth Principle

As Outlined in Senator Proxmire’s Testimony

The fourth principle of the truth-in-lending bill is that its advocates believe in our modified free enterprise system; that we believe in the benefits of a free market in which people may make their own choices knowledgeably and freely as an enduring and efficient basis for our economy. If we think that the market should be governed by the choices made by people, with a minimum of interference, obstruction, or monopoly, then we must support the right of the consumer to know· the full facts so that he can make wise choices.

This principle of the truth-in-lending bill means, therefore, that prices set by American businessmen for interest or credit should not be set arbitrarily by the Federal Government but rather should be determined by the forces of free and open competition. I want to emphasize this point, because I have heard suggestions that the truth in lending bill is the foot in the door to eventual Federal Government determination of allowable rates of interest or finance charge which businessmen may levy on consumer credit.

Nothing could be further from the truth. I repeat again that a basic principle of this bill is that disclosure-just disclosure of the full cost of credit effectively will protect consumers and businessmen. Full disclosure will restore a more free operation of individual choices in the marketplace.

Mr. President, the fourth principle of truth in lending is that ethical businessmen, those who believe in a competitive free enterprise system, and who work to achieve their profits by offering quality and service and not deception or confusion will be aided by full disclosure. Obviously, however, the truth-in-lending bill does not help the unethical businessman who engages in deceiving or confusing or fooling or cheating the credit customer.”

Senator William Proxmire

Senate Testimony

January 31, 1967

BEHIND THE SCENES

The CFPB In Irons, Stakeholders Fight back

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) officially began operations on July 21, 2011. It was established under Title X of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Financial Protection Act (P.L. 111-203), commonly known as the Dodd-Frank Act. The CFPB was created to consolidate various consumer financial protection responsibilities into a single agency.

The purpose of the CFPB, as outlined in the Dodd-Frank Act, is to implement and enforce federal consumer financial laws while ensuring that consumers have access to financial products and services. Additionally, the CFPB is tasked with ensuring that the markets for consumer financial services and products are fair, transparent, and competitive.

To achieve its goals, the CFPB has the authority to issue regulations, examine certain financial institutions, and enforce consumer protection laws and regulations.

Since its operations started, the CFPB has, at times, aggressively pursued legal action in the name of Title X and publically thrashed those who come into its crosshairs. However, since the change of administration and, apparently, under the direction of the White House, the CFPB has gone silent.

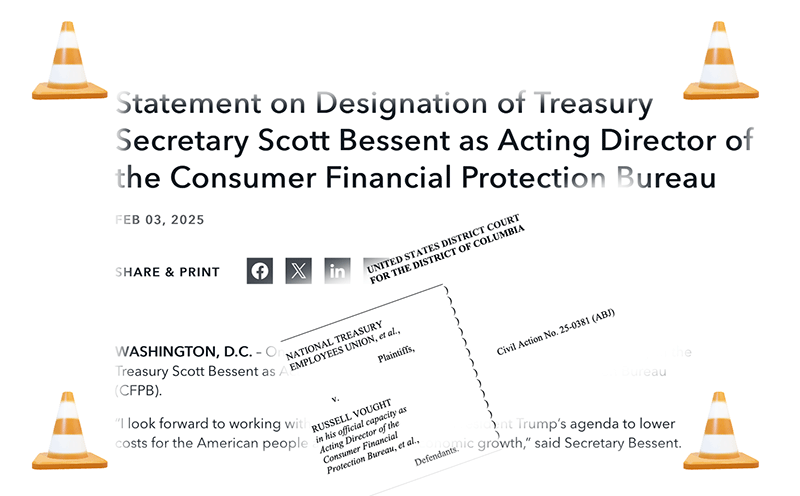

Oddly, the Bureau has abandoned its normal operational tempo, even dropping several pending discrimination and RESPA cases. The CFPB hasn’t even made a press release in over a month, the last being the announcement that Secretary of the Treasury Scott Bessent is now Acting Director.

Strange times indeed. Consider the lawsuit filed on behalf of various stakeholders, including the CFPB Employee Association and the National Treasury Employees Union.

CFPB Employee Union Lawsuit

WASHINGTON, D.C. – Today, the National Treasury Employees Union (NTEU) with Public Citizen Litigation Group and Gupta Wessler LLP, filed a lawsuit against President Trump, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), and CFPB Acting Director Russell Vought, to challenge the unlawful dismantling of the CFPB.

Established by Congress in response to the 2008 financial crisis, the CFPB is tasked with overseeing financial institutions and protecting consumers from predatory practices. Since its inception, the agency has recovered billions of dollars for American citizens and helped create a fairer, more transparent financial marketplace. Congress exercised its constitutional authority to regulate commerce when it created the CFPB, ensuring that it operates independently to fulfill its mandate.

In defiance of Congress’s role in our constitutional system and the separation of powers, President Trump has openly declared his intent to “totally eliminate” the CFPB, and the defendants are acting quickly to carry out that direction. Their actions have caused mass confusion and imposed significant and irreparable harm on consumers across the country.

The lawyers representing the plaintiffs are asking for a temporary restraining order that would keep employees on the job, as intended when Congress passed the Dodd-Frank Act and created the CFPB. CFPB employees are public servants dedicated to being a watchdog against financial fraud and abuse and educating Americans about their rights as consumers.

NTEU represents more than 1,000 frontline employees. “We will not stand by and let this administration destroy the agency that protects seniors, veterans, active-duty military and all American consumers,” said NTEU National President Doreen Greenwald. “The employees of the CFPB are nonpartisan professionals who swore an oath to uphold the Constitution, and they believe in the mission of their agency. Locking them out of their jobs or firing them is a gift to predatory lenders and unscrupulous actors who prey on consumers.”

Commenting on the lawsuit, Public Citizen Litigation Group director Allison Zieve said: “The Trump administration is upending the lives of employees, depriving researchers and the public of important information, and devastating the ability of legal services organizations that depend on the CFPB to provide consumers with the help exercising their rights.”

Deepak Gupta, founding principal of Gupta Wessler LLP and former senior counsel at the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, shared: “This a tragedy for American consumers, and it is lawless. The Bureau was created by Congress to ensure a fair marketplace and protect the financial security of everyday Americans, helping them avoid fraud, predatory lending, and abusive financial practices. The President and his acting director lack the authority to suspend the agency’s work, defund its operations, or halt enforcement of consumer protection laws. We seek an immediate order restoring the CFPB’s operations and emergency relief to prevent further harm to consumers.”

Press Announcement

Tip of the Week – Gifts for Referrals

Question: Can I give gifts to my past customers when they send me a referral?

Answer: Not lawfully.

Gifts are generally considered “things of value” under RESPA Section 8(a). This means they may violate this section if given or accepted as part of an agreement or understanding for referring business related to real estate settlement services involving a federally related mortgage loan. Therefore, such gifts or promotions are prohibited in those circumstances.

RESPA Section 8 prohibitions generally apply to any person, which RESPA defines to include individuals, corporations, associations, partnerships, and trusts. 12 USC § 2602(5).

If a gift is given only to a specific group of past customers who are either current referral sources or a targeted group of potential future referral sources, it may imply that the recipient is receiving the item as a result of previous or future referrals. Therefore, the provision of the gift item could be seen as dependent on making referrals.

There is no exception to RESPA Section 8 solely based on the value of the gift. Accordingly, lenders should carefully analyze whether providing gifts or opportunities to win prizes to referral sources could violate the prohibitions under RESPA Section 8.