Correction!

Last week’s Journal V2I33 N58 article on appraisal risks incorrectly states – “(HPML only applies to owner-occupied and second homes, not investor deals).” That is technically incorrect. HPML does not apply to second homes. 12 CFR § 1026.35(a)(1) “Higher-priced mortgage loan means a closed-end consumer credit transaction secured by the consumer’s principal dwelling.”

However, differentiating a second home from the primary or principal dwelling can involve risk. Therefore, lenders may overlay loan manufacture compliance for second homes as though the transaction is covered. In any event, remember, it is the lender’s prerogative and responsibility to condition for a second appraisal, whether required by law or prudent risk management.

Why Haven’t Loan Officers Been Told These Facts?

The Mindless (But Dangerous) Shuffle Through Key Disclosures and Agreements

A Few Mortgage Fraud Statutes

18 USC §§ 1001 (The one mentioned in the URLA)

Statements or entries

Except as otherwise provided in this section, whoever, in any matter within the jurisdiction of the executive, legislative, or judicial branch of the Government of the United States, knowingly and willfully-

(1) falsifies, conceals, or covers up by any trick, scheme, or device a material fact;

(2) makes any materially false, fictitious, or fraudulent statement or representation; or

(3) makes or uses any false writing or document knowing the same to contain any materially false, fictitious, or fraudulent statement or entry shall be fined under this title, imprisoned not more than five years.

18 USC §1344

Bank fraud

Whoever knowingly executes, or attempts to execute, a scheme or artifice-

(1) to defraud a financial institution; or

(2) to obtain any of the moneys, funds, credits, assets, securities, or other property owned by, or under the custody or control of, a financial institution, by means of false or fraudulent pretenses, representations, or promises; shall be fined not more than $1,000,000 or imprisoned not more than 30 years, or both.

18 USC §1010

Department of Housing and Urban Development and Federal Housing Administration transactions

Whoever, for the purpose of obtaining any loan or advance of credit from any person, partnership, association, or corporation with the intent that such loan or advance of credit shall be offered to or accepted by the Department of Housing and Urban Development for insurance, or for the purpose of obtaining any extension or renewal of any loan, advance of credit, or mortgage insured by such Department, or the acceptance, release, or substitution of any security on such a loan, advance of credit, or for the purpose of influencing in any way the action of such Department, makes, passes, utters, or publishes any statement, knowing the same to be false, or alters, forges, or counterfeits any instrument, paper, or document, or utters, publishes, or passes as true any instrument, paper, or document, knowing it to have been altered, forged, or counterfeited, or willfully overvalues any security, asset, or income, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than two years, or both.

What’s in a name?

During the loan manufacture, the industry has become hypervigilant regarding consumer disclosure and protections to guard against consumer abuse and avoid another 2008. This focus on consumer protection is appropriate in light of the industry’s past failures and inability to self-police. Unfortunately, another culprit threatens the well-being of the mortgage industry besides originators—the applicant.

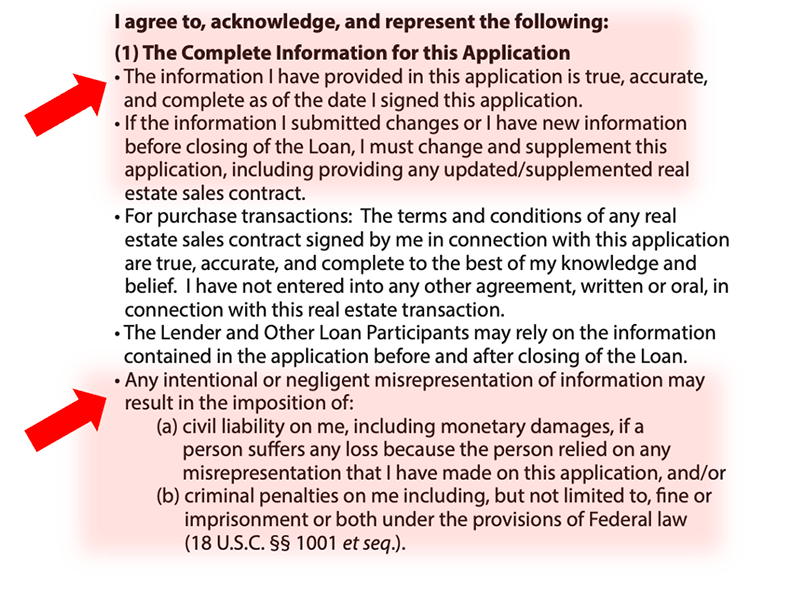

It’s not just the wilful fraudsters that are the problem. Well-intentioned borrowers make unintentional yet material misrepresentations when failing to comprehend the data required for the URLA.

Intentional misrepresentations are not the subject of this writing. Instead, this article focuses on unintentional material misrepresentation or omission. In some quarters, what is called constructive fraud is fraud without the intent to deceive. 18 USC 1001 refers more to actual fraud. So do the other cited federal criminal fraud statutes. However, applicants have plenty of exposure outside of criminal fraud. Constructive fraud in connection with a mortgage application is very serious business with potentially devastating civil liabilities. Of course, another problem could arise, what if the borrower gets indicted for criminal fraud when perhaps a civil charge is appropriate?

Often, the problem begins with data collection, nomenclature, and ignorance. Nevertheless, taking the loan application requires accuracy and attention to detail. The mortgage industry’s viability and integrity rise and fall with a reputation for accurate data used to approve, insure and sell loans. Without accurate data, there is no security in mortgage lending.

However, the sheer volume of agreements, disclosures, and warranties attendant with the loan manufacture tend to numb MLOs and applicants alike to the import of truthfulness and accuracy.

Just as sure as avarice may lead to intentional material misrepresentations, misunderstandings can also land your applicant in hot water.

As is an intentional misrepresentation, reckless treatment of the truth leading to negligent misrepresentation by the applicant is unlawful. For starters, criminal fraud violations are felonies, not misdemeanors. A felony conviction has a high cost. In addition to the financial impacts, felons lose civil rights, licensure, job opportunities, housing opportunities, security clearances, and social standing.

Questions arise regarding the applicant’s intent during a mortgage investigation (investigations are routine for seriously delinquent or defaulted loans). Whether or not the applicant intended to inveigle the lender through misrepresentation or obfuscation of the truth. Appearances matter. A party to an investigation does not get the “benefit of the doubt.”

Mortgage applicants often rely on the MLO to explain, interpret and qualify the importance of disclosures and agreements. The URLA is rife with possibilities for misrepresentations owing to misunderstandings.

From Cornell Law School LII: In civil litigation, allegations of fraud might be based on a misrepresentation of fact that was either intentional or negligent. For a statement to be an intentional misrepresentation, the person who made it must either have known the statement was false or been reckless as to its truth. The speaker must have also intended that the person to whom the statement was made would rely on it. A claim for fraud based on a negligent misrepresentation differs in that the speaker of the false statement may have actually believed it to be true; however, the speaker lacked reasonable grounds for that belief.

Sounds like a loan application. Even if the matter fails to trigger a criminal prosecution, negligent misrepresentation could be very serious for the borrower. However, prosecutors will be prosecutors. How should the state know what was in a person’s head? And there lies a discrete danger: even a negligent misrepresentation could be construed as intentional. Especially when the facts indicate the lender may have taken a different direction in the lending decision if there had been no material misrepresentation.

When the misrepresentation is immaterial to the applicant’s qualification, that isn’t much of a concern. But how convenient for the applicant when in fact, the misrepresentation contributed to a favorable credit decision. That is a concern.

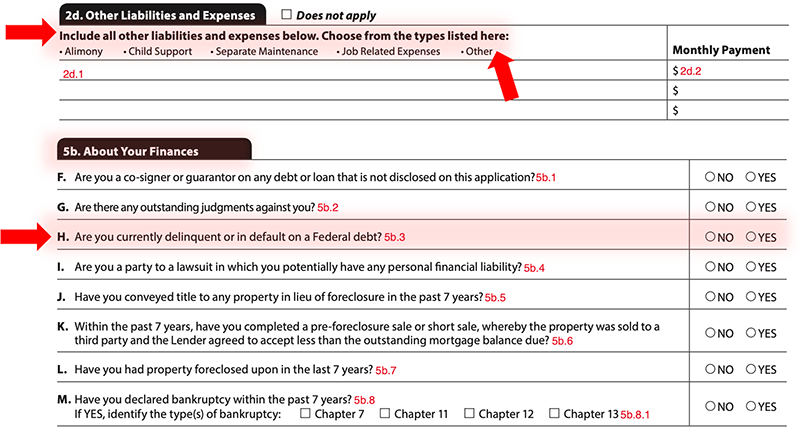

Danger Areas

Of particular concern is the applicant’s liabilities. Liabilities directly impact the lender’s determination of the applicant’s capacity to meet the mortgage terms. Should the applicant fail to grasp the term or meaning of liability, they may fail to address the liability in the application.

Should law enforcement gain knowledge of the nondisclosure of a material fact in connection with a mortgage loan, they may have to prosecute the offender.

The government’s prosecution interest in the matter may hinge on several factors. If there are damages, that is a good place to begin. Furthermore, the more sophisticated the applicant is about the law or mortgage lending, and the more significant the misrepresentation or omission, the greater the likelihood your customer will get indicted. Whether or not a material misrepresentation was wilful is not necessary for the government to prove in a civil matter.

MLOs must emphasize the importance of appropriate disclosure to their customers. When in doubt, list the liability and let the lender sort it out. Better that way than failing to list a liability that should be disclosed.

For example, FNMA treats legally assigned liability differently than other contingent liability. Should a court assign a mortgage liability to one of the parties in a divorce, the creditor may still hold that the other party still has a contingent liability for the mortgage. Nonetheless, FNMA says we don’t have to worry about it.

From FNMA: B3-6-05, Monthly Debt Obligations, “When a borrower has outstanding debt that was assigned to another party by court order (such as under a divorce decree or separation agreement) and the creditor does not release the borrower from liability, the borrower has a contingent liability. The lender is not required to count this contingent liability as part of the borrower’s recurring monthly debt obligations.

The lender is not required to evaluate the payment history for the assigned debt after the effective date of the assignment. The lender cannot disregard the borrower’s payment history for the debt before its assignment.”

FNMA specifies no test for the assignee’s timely payment post-court assignment. Additionally, unlike other potentially contingent liabilities, FNMA requires no evidence of timely payment by the assignee. Nevertheless, FNMA wants the lender to consider whether the applicant was responsible for delinquent payments before the court order. Therefore, the URLA must include the debt. Consequently, the lender does not consider the debt a financial obligation but must consider the loan’s payment history in evaluating credit risk.

How the heck is the applicant supposed to know how to figure out what and how to declare apart from the MLO guidance?

However, business debt in the borrower’s name gets more scrutiny than debt assigned by court order. The lender should list the debt on the URLA and provide evidence for its exclusion from the capacity test. FNMA treats business debt in the borrower’s name like other contingent liability. FNMA also expects the lender to ascertain if the applicant misrepresents the business’s liability for the debt.

B3-6-05, Monthly Debt Obligations

When a self-employed borrower claims that a monthly obligation that appears on his or her personal credit report (such as a Small Business Administration loan) is being paid by the borrower’s business, the lender must confirm that it verified that the obligation was actually paid out of company funds and that this was considered in the lender’s cash flow analysis of the borrower’s business.

From FNMA

The account payment must be considered as part of the borrower’s DTI ratio in any of the following situations:

If the business provides acceptable evidence of its payment of the obligation, but the lender’s cash flow analysis of the business does not reflect any business expense related to the obligation (such as an interest expense—and taxes and insurance, if applicable—equal to or greater than the amount of interest that one would reasonably expect to see given the amount of financing shown on the credit report and the age of the loan). It is reasonable to assume that the obligation has not been accounted for in the cash flow analysis.

Brutally Ambiguous Requirements for Lenders

The FNMA requires the lender to examine the business documents, including returns, to test if the evidence of business payment is legit. FNMA suggests the examiner make some substantive assumptions about the legitimacy of the business’s payment of the debt in question. Without a background in audits or public accounting, the underwriter could quickly be in over their head.

Another area of material misrepresentation is a delinquent federal tax. Technically, the self-employed must pay the taxes owed at least each quarter – not at the end of the year. As such, the self-employed that pay insufficient taxes throughout the year are delinquent. However, since the self-employed need a degree in tax accounting to determine their tax liability, the government treats delinquent tax estimates and insufficient withholdings more lightly.

In contrast, once the taxpayer files the return, taxes that are owed equals taxes that are delinquent. There is no way to hedge around the delinquency issue once the tax returns are filed. IRS tax transcripts reflect delinquent taxes. However, if the return was recently filed, the delinquent taxes may not show in the transcript until the IRS gets to the recently filed return.

Lenders must request IRS “Record of Account Transcript” to obtain the return transcript AND information about delinquent taxes. The IRS “Tax Return Transcript” is just that and does not reflect federal tax debt other than what is reflected in the tax return.

Consequently, MLOs should ask at application if the applicants have filed any returns for which they still have any federal taxes due. For example,” Mr. Borrower, have you filed your 2021 tax return? Great, thank you for that information. May I ask another question about your taxes? Mr. Borrower, do you owe the IRS any taxes for any years you have filed a tax return? That includes 2021 and prior years.”

Frequently, lack of preparation leads to “convenient” omissions and misrepresentations in the URLA. The intentional mortgage fraud for property or intentional misrepresentation to get better financing is a federal criminal offense. Mom and Pop will be sentenced to a federal penitentiary if successfully prosecuted.

Get to consumers early before they get any skin in the game. Emphasize to stakeholders the importance of mortgage planning and preparation.

Check out this high profile ongoing federal mortgage fraud prosecution here. The Journal has discussed this case study before. Remember, don’t confuse the government’s allegations with legal facts. Innocent until proven guilty.

BEHIND THE SCENES

Mortgage Discrimination – The CFPB and DOJ Are Coming For Noncompliant Nonbank Lenders

Another non-bank discrimination case. As you may have heard, the CFPB undertook its first discrimination prosecution of a mortgage broker in an ECOA discouragement lawsuit about two years ago. Last month, the Bureau announced another action. This time against a regional mortgage company.

July 27, 2022

Joint Announcement from the CFPB and DOJ

On July 27, 2022, the Bureau, together with the United States Department of Justice (DOJ), filed a complaint and proposed consent order in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania to resolve their allegations against Trident Mortgage Company, LP (Trident).

Trident is incorporated in Delaware and had locations in Delaware, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania at the time of the alleged conduct. Before the complaint was filed, Trident ceased originating mortgages. The states of Delaware, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania entered into concurrent agreements with Trident.

The Bureau’s and DOJ’s joint complaint alleges that Trident engaged in unlawful discrimination on the basis of race, color, or national origin against applicants and prospective applicants, including by redlining majority-minority neighborhoods in the Philadelphia-Camden-Wilmington, PA-NJ-DE-MD Metropolitan Statistical Area (Philadelphia MSA) and engaged in acts and practices directed at prospective applicants that would discourage prospective applicants from applying for credit in violation of the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA), Regulation B, and the Consumer Financial Protection Act of 2010 (CFPA).

DOJ also alleges that Trident’s conduct violated the Fair Housing Act (FHA). If approved by the court, the proposed consent order would require Trident to invest $18.4 million in a loan subsidy program under which Trident will contract with a lender to increase the credit extended in majority-minority neighborhoods in the Philadelphia MSA and make the loans under the loan subsidy fund. That lender must also maintain at least four licensed branch locations in majority-minority neighborhoods in the Philadelphia MSA. Trident must also fund targeted advertising to generate applications for credit from qualified consumers in majority-minority neighborhoods in the Philadelphia MSA and take other remedial steps to serve the credit needs of majority-minority neighborhoods in the Philadelphia MSA.

Trident must also pay a civil money penalty of $4 million.

July 27, 2022

From the CFPB Director Rohit Chopra

For many years, nonbank lenders have been able to avoid many of the legal obligations and responsibilities of traditional banks. Even the Community Reinvestment Act of 1977, specifically passed to address the consequences of redlining and one of our most important tools for encouraging financial institutions to meet the credit needs of low- and moderate-income neighborhoods, exempts nonbank lenders.

But, let me be clear, nonbank lenders are not, nor have they ever been, exempted from the mandates of the nation’s fair housing and fair lending laws. So, while today’s enforcement action against Trident may mark the first ever nonbank government settlement for redlining, credit discrimination is illegal regardless of whether the lawbreaking company is a traditional bank or a nonbank lender.

Nonbank lenders now originate most mortgages in the United States. In May 2022, the percentage of mortgages originated by nonbank lenders reached 77% of all reported mortgages in the country.1 Accordingly, federal policymakers should continue to consider ways to ensure that every mortgage lender serves qualified applicants, particularly minority applicants residing in neighborhoods that have been historically excluded from equal credit access.

The discriminatory actions of Trident sound the alarm that we cannot rest on laurels or past accomplishments alone. Even in Philadelphia, synonymous with liberty, Trident, for years, felt it could redline with impunity.

However, enforcement alone is not the answer. It’s also important to increase the resources available to states that support their supervision and regulation of nonbank lenders. One area where many states are expanding their own fair lending toolboxes is through community reinvestment laws. Recognizing the limits of federal law, Illinois, Massachusetts, and New York all have state versions of the Community Reinvestment Act that obligate both banks and nonbanks to meet state requirements for investments in underserved communities.

I’m so glad we are here alongside the Attorneys General of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware. They are a testament to the fact that states will continue to play a leading role to right the wrongs of discrimination. To support their efforts, the CFPB has taken steps to ensure states know all the ways that they are entitled to use federal consumer financial protection law to hold bank and nonbank financial institutions accountable.

Mortgage lenders should serve all qualified applicants, regardless of their skin color or the demographics of their neighbors. We will continue to seek new remedies to ensure all lenders meet and fulfill their responsibilities and obligations and the CFPB continues to be on the lookout for emerging digital redlining to ensure that discrimination cannot be disguised by an algorithm.

Thank you. – Rohit Chopra

Tip of the Week – Sex and Familial Discrimination

Last week we covered a Fair Housing Act complaint concerning a lender’s alleged discrimination against an applicant on maternity leave. The FHA 4000.1 describes the income calculus in much the same way as FNMA.

See last week’s Journal for the FHA treatment of income qualification relative to temporary leave. This week, we examine the FNMA guidance.

FNMA requirements for calculating temporary leave income used for qualifying

If the borrower will return to work as of the first mortgage payment date, the lender can consider the borrower’s regular employment income in qualifying.

If the borrower will not return to work as of the first mortgage payment date, the lender must use the lesser of the borrower’s temporary leave income (if any) or regular employment income. If the borrower’s temporary leave income is less than his or her regular employment income, the lender may supplement the temporary leave income with available liquid financial reserves (see B3-4.1-01, Minimum Reserve Requirements). Following are instructions on how to calculate the “supplemental income”:

Supplemental income amount = available liquid reserves divided by the number of months of supplemental income

Available liquid reserves: subtract any funds needed to complete the transaction (down payment, closing costs, other required debt payoff, escrows, and minimum required reserves) from the total verified liquid asset amount.

Number of months of supplemental income: the number of months from the first mortgage payment date to the date the borrower will begin receiving his or her regular employment income, rounded up to the next whole number.

After determining the supplemental income, the lender must calculate the total qualifying income.

Total qualifying income = supplemental income plus the temporary leave income

The total qualifying income that results may not exceed the borrower’s regular employment income.

Example

-

- Regular income amount: $6,000 per month

- Temporary leave income: $2,000 per month

- Total verified liquid assets: $30,000

- Funds needed to complete the transaction: $18,000

- Available liquid reserves: $12,000

- First payment date: July 1

- Date borrower will begin receiving regular employment income: November 1

- Supplemental income: $12,000/4 = $3,000

Total qualifying income: $3,000 + $2,000 = $5,000