Why Haven’t Loan Officers Been Told These Facts?

Adverse Action Requirements – The CFPB Clarifies Use of the Model Adverse Action Form

The CFPB states in Appendix C to Regulation B, regarding their adverse action notice examples, that the “sample forms are illustrative and may not be appropriate for all creditors. They were designed to include some of the factors that creditors most commonly consider. If the reasons listed on the forms are not the factors actually used, a creditor will not satisfy the notice requirement by simply checking the closest identifiable factor listed.”

However, as stated in the Appendix C narrative, the wooden use of the adverse action sample forms will not likely satisfy ECOA notice requirements. The notice requirements can be complex.

Unlike Regulation Z, which defines an application as including identified property, the Regulation B application definition has no such requirement.

This application distinction is essential, as preapprovals are applications under Regulation B and are subject to the notice requirements. But don’t conflate or confuse the regulatory requirements. To clarify, Regulation B does not govern the Regulation Z disclosure requirements. For example, on a preapproval, the lender must provide a notice of action yet is not required to provide the Loan Estimate.

Reg B 12 CFR § 1002.2(f) . . . Application means an oral or written request for an extension of credit that is made in accordance with procedures used by a creditor for the type of credit requested.

As implemented by Regulation Z, the TILA attenuates the risk of the uninformed use of consumer credit by requiring written disclosure and intent to proceed before putting the consumer at risk. If no property is identified, there is no risk of the uninformed use of mortgage credit, including the legal obligations, potentially toxic financing features, or costs surrounding a mortgage [No property means no mortgage].

Reg Z 12 CFR § 1026.2(a)(2) An application means the submission of a consumer’s financial information for purposes of obtaining an extension of credit. For transactions subject to the Loan Estimate disclosure, the term consists of the consumer’s name, the consumer’s income, the consumer’s social security number to obtain a credit report, the property address, an estimate of the value of the property, and the mortgage loan amount sought.

The ECOA, as implemented by Regulation B, has a different objective than TILA. The ECOA mitigates uncertainty surrounding unlawful discriminatory practices. At least, that is the intent. Consequently, Regulation B describes an application and the lender’s notice obligations quite differently. Prequalifications can become an application depending on the lender’s behavior and need not identify a property.

An Application Occurs When Taking Adverse Action

Comment 2(f)-3 However, if in giving information to the consumer the creditor also evaluates information about the consumer, decides to decline the request, and communicates this to the consumer, the creditor has treated the inquiry or prequalification request as an application and must then comply with the notification requirements under § 1002.9.

Regulation B Could Better Define Application and Preapproval

Official Comment 2(f)-5.i Examples of an application. An application for credit includes the following situations:

i. A person asks a financial institution to “preapprove” her for a loan (for example, to finance a house or a vehicle she plans to buy) and the institution reviews the request under a program in which the institution, after a comprehensive analysis of her creditworthiness, issues a written commitment valid for a designated period of time to extend a loan up to a specified amount. . . But if the creditor’s program does not provide for giving written commitments, requests for preapprovals are treated as prequalification requests for purposes of the regulation.

Written commitment is undefined in the regulation, and preapproval, other than the limited mention in the official commentary, needs to be better distinguished from prequalification. Yet Regulation B implies that the preapproval letters that lenders routinely distribute to stakeholders likely satisfy the criteria for written commitments.

Comment 9(_)-5. Prequalification requests. Whether a creditor must provide a notice of action taken for a prequalification request depends on the creditor’s response to the request, as discussed in comment 2(f)-3. For instance, a creditor may treat the request as an inquiry if the creditor evaluates specific information about the consumer and tells the consumer the loan amount, rate, and other terms of credit the consumer could qualify for under various loan programs, explaining the process the consumer must follow to submit a mortgage application and the information the creditor will analyze in reaching a credit decision.

To work through the prequalification preapproval question, next time you write a preapproval letter, consider the verbiage from the Regulation B definition for prequalification. “the loan amount, rate, and other terms of credit the consumer could qualify for.”

For example, “ABC Mortgage has not received an application from you. However, ABC Mortgage has explained to you the loan amount you COULD qualify for based on information you supplied to ABC Mortgage.” In many markets, that “preapproval letter” will go over like a turd in the punchbowl.

Lame or uncommitted language is exactly why lenders (including brokers) craft their preapproval letters to convey the rigor of their credit analysis and conclusions. The commentary’s example makes clear that no application occurs during a prequalification. You can’t have it both ways. The prequalification features commentary mentions “explaining the process the consumer must follow to submit a mortgage application.”

It’s easy to miss the forest for the trees. Keep in mind the salient objectives of the ECOA. The ECOA seeks to deter and make manifest unlawful discriminatory behaviors. If a lender can interpret the notice and reporting rules loosely or to fit their own agenda, the ECOA and HMDA are rendered useless.

From the CFPB Adverse Action Circular

Does CFPB’s Model Adverse Action Checklist Satisfy the ECOA Notice Requirements?

Question:

When using artificial intelligence or complex credit models, may creditors rely on the checklist of reasons provided in CFPB sample forms for adverse action notices even when those sample reasons do not accurately or specifically identify the reasons for the adverse action?

Answer:

No, creditors may not rely on the checklist of reasons provided in the sample forms (currently codified in Regulation B) to satisfy their obligations under ECOA if those reasons do not specifically and accurately indicate the principal reason(s) for the adverse action. Nor, as a general matter, may creditors rely on overly broad or vague reasons to the extent that they obscure the specific and accurate reasons relied upon.

ECOA and Regulation B require that, when taking adverse action against an applicant, a creditor must provide the applicant with a statement of reasons for the action taken. This statement of reasons must be “specific” and indicate the “principal reason(s) for the adverse action”; moreover, the specific reasons disclosed must “relate to and accurately describe the factors actually considered or scored by a creditor.” Adverse action notice requirements promote fairness and equal opportunity for consumers engaged in credit transactions, by serving as a tool to prevent and identify discrimination through the requirement that creditors must affirmatively explain their decisions. In addition, such notices provide consumers with a key educational tool allowing them to understand the reasons for a creditor’s action and take steps to improve their credit status or rectify mistakes made by creditors.

The CFPB provides sample forms (currently codified in Regulation B) that creditors may use to satisfy their adverse action notification requirements, if appropriate. These forms include a checklist of sample reasons for adverse action which “creditors most commonly consider,” as well as an open-ended field for creditors to provide other reasons not listed. The sample forms are used by creditors to satisfy certain adverse action notice requirements under ECOA and the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA), though the statutory obligations under each remain distinct. While the sample forms provide examples of commonly considered reasons for taking adverse action, “[t]he sample forms are illustrative and may not be appropriate for all creditors.” Reliance on the checklist of reasons provided in the sample forms will satisfy a creditor’s adverse action notification requirements only if the reasons disclosed are specific and indicate the principal reason(s) for the adverse action taken.

Because it is unlawful for a creditor to fail to provide a statement of specific reasons for the action taken, a creditor will not be in compliance with the law by disclosing reasons that are overly broad, vague, or otherwise fail to inform the applicant of the specific and principal reason(s) for an adverse action. Just as an accurate description of the factors actually considered or scored by a creditor is critical to ensuring compliant adverse action notifications, sufficient specificity is also required. Such specificity is necessary to ensure consumer understanding is not hindered by explanations that obfuscate the principal reason(s) for the adverse action taken.

Appendix C to Part 1002 — Sample Notification Forms

3. The sample forms are illustrative and may not be appropriate for all creditors. They were designed to include some of the factors that creditors most commonly consider. If a creditor chooses to use the checklist of reasons provided in one of the sample forms in this appendix and if reasons commonly used by the creditor are not provided on the form, the creditor should modify the checklist by substituting or adding other reasons. For example, if “inadequate down payment” or “no deposit relationship with us” are common reasons for taking adverse action on an application, the creditor ought to add or substitute such reasons for those presently contained on the sample forms.

4. If the reasons listed on the forms are not the factors actually used, a creditor will not satisfy the notice requirement by simply checking the closest identifiable factor listed. For example, some creditors consider only references from banks or other depository institutions and disregard finance company references altogether; their statement of reasons should disclose “insufficient bank references,” not “insufficient credit references.” Similarly, a creditor that considers bank references and other credit references as distinct factors should treat the two factors separately and disclose them as appropriate. The creditor should either add such other factors to the form or check “other” and include the appropriate explanation. The creditor need not, however, describe how or why a factor adversely affected the application. For example, the notice may say “length of residence” rather than “too short a period of residence.”

Note that Regulation B does not require that a lender must “when taking adverse action against an applicant, a creditor must provide the applicant with a statement of reasons for the action taken.”

12 CFR § 1002.9(a)(2) Content of notification when adverse action is taken.

A notification given to an applicant when adverse action is taken shall be in writing [Subject to E-SIGN compliance, may be electronically transmitted] and shall contain a statement of the action taken; the name and address of the creditor; a statement of the provisions of section 701(a) of the Act [ECOA Notice]; the name and address of the Federal agency that administers compliance with respect to the creditor [Federal Trade Commission for nondepository lenders]; and either:

A statement of specific reasons for the action taken;

[OR]

(ii) A disclosure of the applicant’s right to a statement of specific reasons within 30 days, if the statement is requested within 60 days of the creditor’s notification.

The disclosure shall include the name, address, and telephone number of the person or office from which the statement of reasons can be obtained.

If the creditor chooses to provide the reasons orally, the creditor shall also disclose the applicant’s right to have them confirmed in writing within 30 days of receiving the applicant’s written request for confirmation.

See the entire CFPB 2023-03 Circular adverse action notification requirements below.

2023-03 Adverse Action Notice

Do you have a great value proposition you’d like to get in front of thousands of loan officers? Are you looking for talent?

BEHIND THE SCENES – HMDA Beat Down, Bank of America MLOs Allegedly Falsify HMDA Data

WASHINGTON, D.C. – The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) today ordered Bank of America to pay a $12 million penalty for submitting false mortgage lending information to the federal government under a long-standing federal law. For at least four years, hundreds of Bank of America loan officers failed to ask mortgage applicants certain demographic questions as required under federal law, and then falsely reported that the applicants had chosen not to respond. Under the CFPB’s order, Bank of America must pay $12 million into the CFPB’s victims relief fund.

“Bank of America violated a federal law that thousands of mortgage lenders have routinely followed for decades,” said CFPB Director Rohit Chopra. “It is illegal to report false information to federal regulators, and we will be taking additional steps to ensure that Bank of America stops breaking the law.”

Bank of America (NYSE:BAC) is a global systemically important bank headquartered in Charlotte, North Carolina. As of June 2023, the bank had $2.4 trillion in assets, which makes it the second-largest bank in the United States.

Enacted in 1975, the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) requires mortgage lenders to report information about loan applications and originations to the CFPB and other federal regulators. The data collected under HMDA are the most comprehensive source of publicly available information on the U.S. mortgage market. The public and regulators can use the information to monitor whether financial institutions are serving the housing needs of their communities, and to identify possible discriminatory lending patterns.

The Home Mortgage Disclosure Act requires financial institutions to report demographic data about mortgage applicants. The CFPB’s review of Bank of America’s HMDA data collection practices found that the bank was submitting false data, including falsely reporting that mortgage applicants were declining to answer demographic questions. This conduct violated HMDA and its implementing regulation, Regulation C, as well as the Consumer Financial Protection Act. Specifically, the CFPB found that Bank of America:

- Falsely reported that applicants declined to provide information: Hundreds of Bank of America loan officers reported that 100% of mortgage applicants chose not to provide their demographic data over at least a three month period. In fact, these loan officers were not asking applicants for demographic data, but instead were falsely recording that the applicants chose not to provide the information.

- Failed to adequately oversee accurate data collection: Bank of America did not ensure that its mortgage loan officers accurately collected and reported the demographic data required under HMDA. For example, the bank identified that many loan officers receiving applications by phone were failing to collect the required data as early as 2013, but the bank turned a blind eye for years despite knowledge of the problem.

The CFPB has taken numerous actions against Bank of America for violating federal law. In July 2023, the CFPB and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) ordered Bank of America to pay over $200 million for illegally charging junk fees, withholding credit card rewards, and opening fake accounts. In 2022, CFPB and OCC ordered Bank of America to pay $225 million in fines and refund hundreds of millions of dollars to consumers for botched disbursement of state unemployment benefits. That same year, Bank of America also paid a $10 million penalty for unlawful garnishments of customer accounts. And in 2014, the CFPB ordered Bank of America to pay $727 million to consumers for illegal and deceptive credit card marketing practices.

Enforcement Action

Under the Consumer Financial Protection Act (CFPA), the CFPB has the authority to take action against financial institutions violating consumer financial laws, including HMDA and Regulation C.

Today’s order requires Bank of America to take steps to avoid its illegal mortgage data reporting practices and to pay a $12 million penalty to the CFPB’s victims relief fund.

FNMA/FHLMC URLA Instructions

Tip of the Week – IRS Account Information

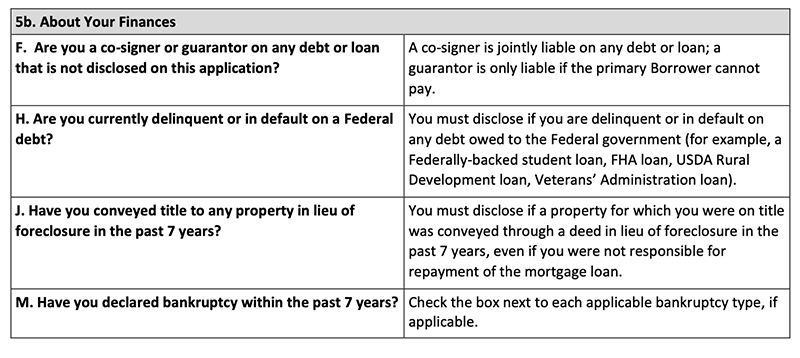

When completing the URLA section 5, applicants and MLOs must be circumspect to provide the correct responses. One particular declaration can be messy for some applicants – delinquent federal debt.

The 1003 fails to define federal debt. While the GSE’s URLA instructions provide claims paid against government-insured loans as an example, other authoritative stakeholders like the FHA Inspector General and Office of Management and Budget include other examples beyond guaranteed loan claims.

5(H). Are you currently delinquent or in default on a Federal debt?

In theory, a person could be delinquent on federal taxes by failing to pay the appropriate estimated tax installments for the current year. If a person egregiously underpaid their current tax estimates, that could be a 5(H) issue, but that is beyond this article’s scope.

More concerning is the inescapable obligation to affirm delinquent federal debt by the applicant who filed their tax return without paying the taxes due or has received notice from the IRS that they owe money. It is a material misrepresentation for these applicants to deny their delinquent federal debt during a mortgage application.

Section 6 Acknowledgments and Agreements, No Minor Matter

I agree to, acknowledge, and represent the following:

(1) The Complete Information for this Application

The information I have provided in this application is true, accurate, and complete as of the date I signed this application. If the information I submitted changes or I have new information before closing of the Loan, I must change and supplement this application, including providing any updated/supplemented real estate sales contract.

Any intentional or negligent misrepresentation of information may result in the imposition of:

(a) civil liability on me, including monetary damages, if a person suffers any loss because the person relied on any misrepresentation that I have made on this application, and/or (b) criminal penalties on me including, but not limited to, fine or imprisonment or both under the provisions of Federal law

(18 U.S.C. §§ 1001 et seq.).

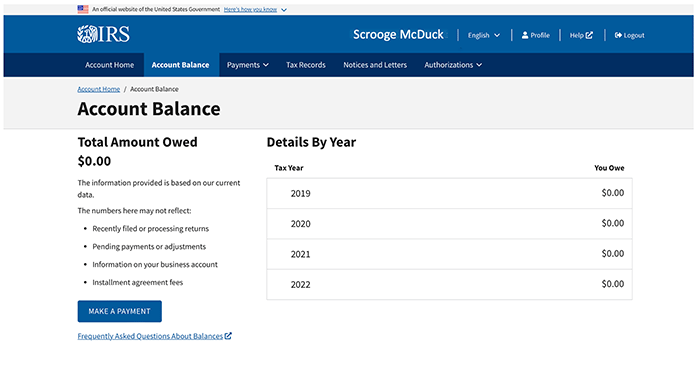

IRS Account Information

IRS tax transcripts have become a standard for loan manufacture quality assurance. But IRS account information has not. What is the difference? The transcript is evidence of the filed tax return, not necessarily the outstanding federal obligation.

A person can obtain their tax transcripts and account information at no cost to determine if the federal government has any tax claims against them.

Persons may also see the details of their IRS payment plan on the IRS website.

Try it out for yourself.

HUDIG 2019 FHA loans to tax debtor’s report